For quite some time now, many researchers have suggested that we exaggerate the dangers of dietary cholesterol. Today, medical science has rehabilitated cholesterol-containing foods and is ready to confirm the benefits of this compound for our health.

A middle-aged American doctor once, while traveling in France, found himself on the verge of depression; he could not resist decadent duck pâtés, live cheeses and other Burgundy meats, but every afternoon, tormented by remorse, he drank a double dose statins — cholesterol-lowering pills.

Karen Shahinyan

Science journalist, editor-in-chief of the LCHF.RU project.

It was six years ago when doctors, science journalists, and most people considered cholesterol-rich foods to be pure evil and the main cause of cardiovascular disease. Even then, many researchers cautiously expressed the opinion that we do not fully understand cholesterol metabolism and exaggerate its danger, but this was still a marginal point of view. Since then, medical science has rehabilitated cholesterol-rich foods.

Cholesterol is the main building material for the body

You need to understand that cholesterol — it is not a poison at all, but, on the contrary, a vital compound, without which not a single cell in our body can do. Membranes are built from cholesterol, that is, cell membranes and internal structures of cells. It is on the membranes that all processes take place, in other words, the whole life of cells. No cholesterol — no life.

Steroid hormones are also produced from cholesterol, including sex hormones - estrogen and testosterone. This may explain why cholesterol-lowering statins also reduce sexuality.

Cholesterol in the body and in food — it's far from the same. Only a quarter of the cholesterol that our body needs (that is, approximately 300-500 mg per day) we get from food, and our body produces another three quarters (about a gram) itself, from scratch. To make it clearer, in total, the human body contains 30-40 grams of pure cholesterol, mainly in cell membranes. That is, every day the body produces a lot of cholesterol on its own, and the value of small doses that come with food, to put it mildly, is exaggerated. If we try to eat less cholesterol-rich foods, the body gains momentum and produces more cholesterol itself — that's all.

There is a big difference between the cholesterol that is stored in the cells and that which floats in the blood. The level of cholesterol in arterial blood plasma, which is measured in laboratory tests, says little about cellular cholesterol.

All cells, without exception, are capable of producing this molecule, about 20 percent of cholesterol is synthesized in the liver, the remaining 80 percent — in all other organs. Synthesis consists of dozens of reactions, they involve a huge number of enzymes.

There is an important nuance: only free (non-esterified) cholesterol can be absorbed in the intestine, while most of the cholesterol in food — it's just related. This fact should be taken into account by everyone who is closely looking for the content of cholesterol on the label. The value that you find there can be safely divided in half. In fairness, pancreatic enzymes can cut off all the excess from bound cholesterol so that it is absorbed in the intestines.

85 percent of unbound cholesterol in the intestines did not come from food, but was formed in the cells of the body, entered the liver with the bloodstream and then excreted into the intestines with bile. Some of this own cholesterol is absorbed through the intestinal wall back into the blood. Thus, most of the cholesterol in the body was synthesized in it and absorbed again, i.e. it's twice your own cholesterol. Why is this needed? Just to save money: our frugal organism re-eats the cholesterol that it has produced, so as not to throw it away in vain.

This once again highlights how important cholesterol is for life. Otherwise, nature would not have created so many intricate ways to synthesize and maintain a constant level of cholesterol, to extract it from food. There are different forms of cholesterol in foods, and not all cholesterol from food is absorbed by the body. All modern scientific evidence suggests that the cholesterol that we consume with food does not particularly affect the quantity and quality of cholesterol in the blood and in general in the body. This is not a private opinion, but a fact that has been repeatedly confirmed in various independent scientific papers.

What can be bad cholesterol?

In the ranking of popular misconceptions compiled by Dr. Peter Athiya, the idea that fatty foods make us fat is at the top of the list. An honorable second place belongs to the theory that cholesterol is harmful. Nothing is further from the truth.

The problem with popular science simplifications is that sometimes they distort the essence. In particular, the favorite names "good" and "bad" cholesterol are very misleading, because there is no such thing as "bad" cholesterol. The negative role of cholesterol is that it can settle on the walls of blood vessels and trigger a cascade of inflammatory reactions, as a result, the lumen of the vessel decreases and blood flow becomes more difficult. However, by the level of cholesterol in the blood it is impossible to determine what it is exactly, how bad it is and where it will be — on the walls of blood vessels or in cell membranes. Elevated levels of cholesterol in the blood can, to some extent, significantly increase the risk of heart disease. However, total cholesterol — too simplistic little to say about the risks of cardiovascular disease. It's easy to say "high cholesterol is bad" and to ban any food that contains cholesterol. The harm of this simplification is that simply banning dietary cholesterol will not reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.

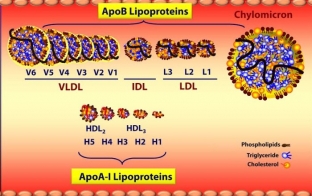

Here we can not do without some physiological details. In the blood, cholesterol is present in packaged form. Pure cholesterol could not dissolve in the blood, just as oil does not dissolve in water. To dissolve and move easily with the bloodstream, cholesterol binds to proteins — lipoproteins are produced. They can be of different density, hence the names that are often found in texts about health — high density lipoproteins (HDL), low density lipoproteins (LDL), and very low density lipoproteins (VLDL). People call HDL "good" cholesterol, and LDL — "bad". It is also an outdated, oversimplified picture that is far from reality. Cholesterol packed in lipoproteins moves from the intestines and liver to the muscles and peripheral organs, and back — from all organs to the liver. The division into two, three or even five types of lipoproteins is conditional — it is important to understand that transport packages in which fats and cholesterol are present in the blood are of greater or lesser density and size:

As you can see in the slide taken from Peter Athiya's blog, LDL is much larger and carries more fat and cholesterol than high-density lipoproteins. These are such hefty tankers that carry not only cholesterol, but also other compounds (fatty acids, for example) that serve as fuel for cells. HDL is tiny compared to them and mostly consists of cholesterol — they are needed in order to transfer it to adipose tissue, to the glands that make steroid hormones from cholesterol, and also back to the liver, from where cholesterol is then excreted into the intestines. It used to be that small HDL is good because it removes cholesterol from the body. However, according to modern scientific concepts, "bad" LDL also transfers cholesterol from the periphery to the liver, in order to then remove it from the body with bile. So that,

The problem with it is that it is LDL that can settle on the walls of blood vessels, because such particles are poorly soluble in the blood, and then they form the notorious atherosclerotic plaques. This property of LDL to precipitate on the walls of blood vessels has become the nightmare of all advocates of healthy eating in the last thirty years. Leading health programs on the central channels, raising their eyebrows, talk about how cholesterol from food instantly clogs the coronary arteries, and a person dies of a heart attack. However, as can be seen from all of the above, this simple and terrible scheme has nothing to do with reality.Cardiovascular disease and cholesterol

The level of total cholesterol generally cannot be used to judge the risk of cardiovascular diseases: more than half of the people admitted to hospitals with a heart attack have normal cholesterol levels, and, conversely, about half of people with high cholesterol live a normal life with clean blood vessels without the slightest hint of atherosclerosis.

Of all the intricate lipid profile, the most important factor that is truly associated with the risk of cardiovascular disease, — is an increased amount of LDL. If there are a lot of them, then there is a risk of developing atherosclerosis. Everything else is secondary, vague and not fully understood. Many statins increase HDL levels, but no one has yet been able to prove whether there is a real benefit from this. The size of LDL does not play a role in this (as you can see on the slide above, they also differ from each other), only their number is important — the more the worse.

High-density lipoproteins (HDL) are really important, and it is better to have more of them in the blood. However, if you omit the complex biochemical nuances, it is important to know that an artificial increase in HDL in the blood does not solve the problem and does not reduce the risk of atherosclerosis with all the ensuing consequences.

Which is more dangerous for the heart, fatty or sweet?

There are no long-term studies that would answer the question of interest to everyone: how will the risk of cardiovascular studies change if eating style is changed? Science does not yet give an honest answer to this question.

In most countries, dietary recommendations are made with a greater or lesser degree of cholesterolophobia. With the exception of the Swedish nutritionists, who were the first to formally recognize animal fats as harmless, all other nutritionists talk about limiting dietary cholesterol, although there is no evidence that dietary saturated fats themselves have any effect on the risk of cardiovascular disease.

However, there are studies that already in the short term show how dangerous sugars can be in this sense. For example, there is evidence that consumption of sugar (or high-fructose corn syrup) increases triglycerides and low-density lipoprotein (LDL, the ones associated with the risk of atherosclerosis), and lowers HDL (those that are considered "good" cholesterol) . And if you exclude sugar (in the study, these were sweetened drinks), then everything changes exactly the opposite: the level of LDL (those that are associated with the risk of vascular pathologies) drops, and the level of HDL — is growing. Pure fructose has a better effect on the ratio of lipoproteins than sugar.

Another study looked at the effects of saturated fat on various lipoprotein levels and overall health. It turned out that adding fat to the diet in the absence of sugar and starch did not increase either the level of triglycerides in the blood, or any other indicators associated with cardiovascular disease. In other words, fatty foods alone do not increase the risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease unless sugar and starchy foods are eaten.

Statins — cholesterol-lowering drugs

Generally, published studies that prove the benefits of statins are funded by the manufacturing companies. The problem is that pharmaceutical companies want to sell as many statins as possible — not only for those who really need them, but for everyone.

Statins — one of the most popular drugs today, their market in America alone is estimated at $30 billion. One in three takes them, although there is no hard scientific evidence that the benefits of statins outweigh the potential risks associated with them. Very common side effects — this is a gradually developing muscle pain and weakness caused by micro-inflammation in the muscles. The consequences are less frequent and more serious — memory lapses and diabetes, so in 2012 the US FDA added them to the list of side effects of statins. The fact is that statins can indirectly not have the best effect on carbohydrate metabolism, since the production of insulin in the pancreas — it is a complex process that is sensitive to the level of cholesterol in the blood.

1. There is no evidence that animal fats cause cardiovascular disease.

2. Carbohydrates, not fats from food, provoke an increase in LDL and triglycerides in the blood.

3. The main role in the development of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases is played not by cholesterol, but by oxidation, inflammation and stress.

Add a comment